![]()

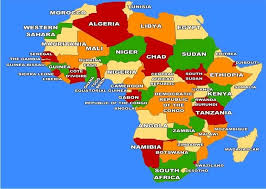

In October 2025, the World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for Africa released a stark finding. About 150 million people across the African continent are living with mental health conditions, such as depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders. This figure, drawn from the region’s new mental health dashboard, should serve as a wake‑up call for policymakers, health professionals, and the public alike. It reveals not just a vast burden of psychological distress, but a profound failure to provide accessible, effective care for people across the continent. To put the scale in context, the African Region comprises 47 countries, with populations both young and growing rapidly. Across this vast territory, mental health conditions touch individuals in every community, from bustling cities to remote rural areas. Yet mental health services remain severely under‑resourced, fragmented, and inaccessible, particularly outside major urban centers.

This gap in care makes Africa’s mental health crisis invisible in its severity. While infectious diseases like malaria and HIV have long dominated public health priorities, with good reason, mental illness has too often been relegated to the margins. Mental health matters because it affects how people think, feel, and function; its neglect has real human consequences for families, workplaces, and societies. A closer look at the statistics paints an even more troubling picture. Suicide remains a major concern in the region, with a regional age‑standardized suicide rate of 11.5 per 100,000 population, higher than the global average in many contexts. Alcohol consumption patterns in some countries exceed 10 liters per capita, which further exacerbates mental health risks and treatment. Only 9 countries in the African Region report having dedicated mental health budget lines, and many lack national policies or trained professionals altogether. These figures are not abstract. They represent real people whose lives are disrupted by conditions that are both common and, in many cases, treatable. For instance, in Nigeria, estimates suggest that about 1 in 4 people may experience some form of mental illness in their lifetime. Yet the country has only a few hundred psychiatrists serving a population of nearly 200 million, leaving about 80% of people with serious mental illness without adequate treatment.

The reasons for this gap are structural and persistent. Mental health receives an extremely low share of health spending in many African countries, often less than US$ 0.50 per person per year, far below recommended levels for effective care. Without meaningful investment, services remain concentrated in psychiatric institutions in major cities, far from the primary and community‑level care where most people could be reached. Beyond funding, stigma and cultural perceptions continue to undermine efforts to address mental illness. In many communities, symptoms of anxiety, depression, or psychosis are attributed to supernatural causes or moral weakness. This not only prevents people from seeking help but also discourages governments from treating mental health as a legitimate public health priority. The result is a self‑reinforcing cycle; low recognition leads to underfunding, which leads to poor data, which in turn leads to continued neglect.

These challenges are compounded by Africa’s unique social and economic pressures. Youth unemployment, poverty, and rapid urbanization are not merely demographic trends; they are lived realities that strain psychological well‑being. For adolescents and young adults, the transition to adulthood often occurs in environments with limited opportunities and high social stress, which increases vulnerability to mental health conditions. Also, research shows that half of all mental health conditions begin by age 14 and 75% by the mid‑20s, a pattern that holds in African populations as well. International comparisons highlight the inequity. While mental health challenges are global, with more than 1 billion people worldwide affected, the gap in treatment access between high‑income and low‑income countries is dramatic. In wealthier settings, around 50% of individuals with mental health disorders receive some form of care; in many African contexts, fewer than 10% do.

The human and economic toll of this gap is immense. Untreated mental illness diminishes productivity, hampers educational attainment, and strains families who often shoulder the burden of care without support. It also intersects with other public health challenges: people with untreated depression are more likely to suffer from chronic physical conditions, substance abuse, or social isolation, creating complex care needs that health systems are ill‑equipped to manage. Yet acknowledging the scale of the problem is only the first step. What Africa needs now are bold investments in community-based services, the integration of mental health into primary healthcare, and targeted efforts to reduce stigma. Policies must be backed by resources, from training more mental health professionals to ensuring that care is affordable, culturally sensitive, and available at the community level. The story of mental health in Africa should not be one of inevitable crises but of urgent action. Nearly 150 million lives are shaped by conditions that deserve attention, understanding, and evidence-based care. Without that, the invisible burden of mental illness will continue to undermine the potential of individuals and societies across the continent.