![]()

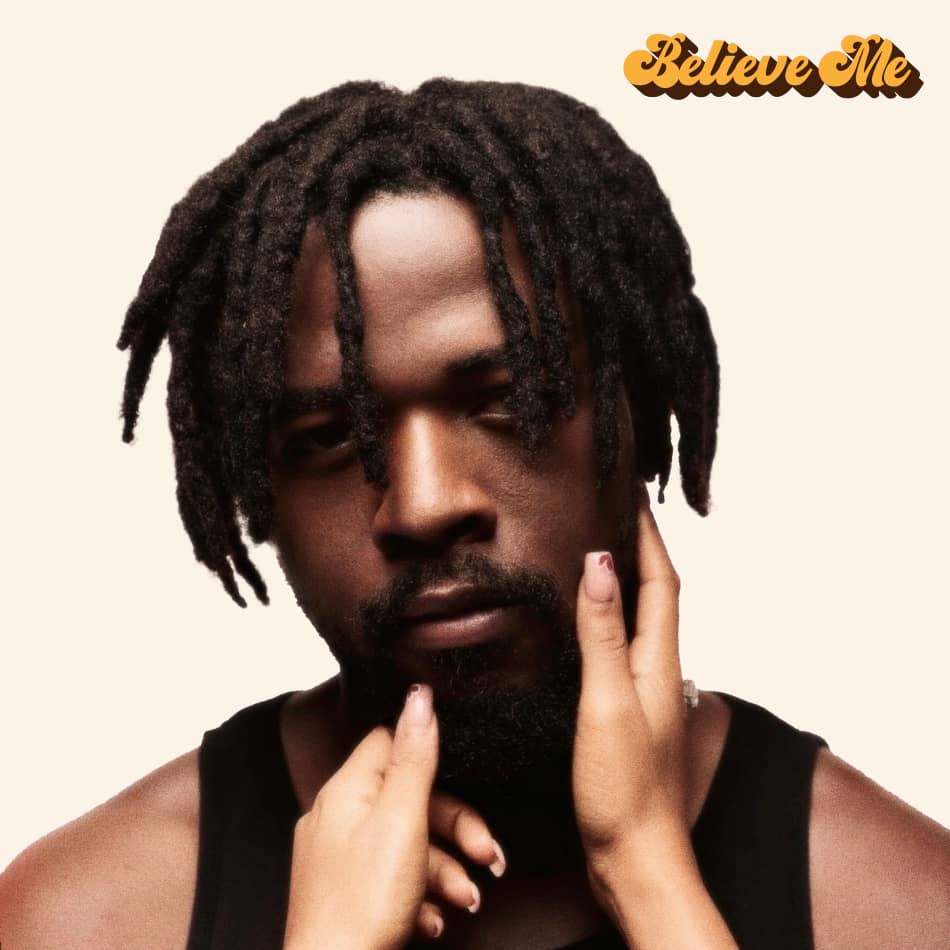

Sade is my name, and I am living life in my mid-thirties. For a long time, I believed I was in love with Johnny Drille. Yes, I love his songs, and he is my type of man. Other girls may desire him, but I didn’t care, for I believed he belonged to me. At the time, the feeling did not seem strange or excessive to me—it felt profound, purposeful, and certain. I was convinced that what I felt was real love, and that somehow, in ways I could not fully explain, it was shared.

Looking back now, with clarity that I did not have then, I understand that what I experienced was not love but a delusion.

During that period, my thoughts revolved almost entirely around him. I interpreted his public presence, his words, songs, and even events that had nothing to do with me as meaningful signs. Ordinary coincidences felt extraordinary. Silence felt intentional. Distance felt temporary. In my mind, everything pointed toward an inevitable meeting, an eventual recognition.

I reorganized my life around this belief. I altered my routines, made plans that no longer aligned with my real circumstances, and held onto hope even when there was no objective reason to do so. I believed that if I showed enough devotion, patience, or personal sacrifice, I would somehow find his favor. I thought endurance itself was proof of love.

I now recognize how much of my behavior was driven by interpretation rather than reality. I was not responding to a relationship, but to an internal narrative that felt emotionally convincing. I did not question it because questioning it felt like betrayal—of him, and of myself.

What is difficult to admit is that my certainty protected me from deeper pain. It shielded me from loneliness, from unresolved longing, from unmet emotional needs. The belief gave my suffering a direction and my life a focus. It was easier to believe I was chosen than to confront how disconnected I felt from myself and others.

When I finally received psychiatric help, I did not immediately accept the explanation offered to me. At first, I defended my belief with logic that only made sense inside my own emotional framework. But slowly—through therapy, medication, and sustained reflection—the intensity began to loosen.

There was no sudden collapse of the delusion. Instead, there were moments of doubt. Questions I had previously avoided. Contradictions I could no longer explain away.

The most painful realization came when I understood that love requires mutual presence, consent, and shared reality. What I had experienced was intense emotion without relationship, longing without reciprocity. My feelings were real, but their meaning was not what I believed.

Accepting this was not humiliating—it was grieving. I mourned the time, the energy, and the version of myself that lived inside that belief. I also mourned the fantasy of being seen, chosen, and understood without having to risk real vulnerability.

Today, I can say with honesty that I was never in love with Johnny, yes, I am a fan, and he blows me away. I was in the grip of a delusion shaped by my psychological needs at the time. That does not make me foolish or weak—it makes me human and unwell at that point in my life.

Recovery, for me, has not meant erasing the experience, but integrating it. I can now distinguish between emotional intensity and emotional truth. I am learning to form connections grounded in reality, where love grows from shared presence rather than imagined destiny.

Most importantly, I have learned compassion for myself—the person I was when my mind was trying, imperfectly, to survive.

I know I will find love with a choice made out of a sane mind

Account Written and Adapted by

Dr Owoeye Oluwatobi Ajibola

Psychiatrist

08131860275